The Ego, the Fighter, and the Dancer

I have had an issue with a particular grade in climbing. It’s not the hardest grade I climb, nor is it the easiest. The problem revolves around routes that I can do quickly, but are challenging enough to make me want to tick them on 8a.nu or Mountain Project.

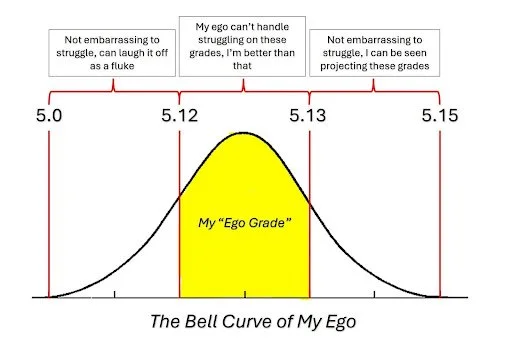

I call this the “Ego Grade”. For me, that includes sport routes between 12a and 13a. While on a climbing trip last year, I realized that this relationship with the “ego grade” was holding me back from becoming a better, happier climber.

Coach Casey Elliott at Star Wall, California

What’s an Ego Grade?

What is an “Ego Grade”?

Simply, an Ego Grade is a climbing grade that boosts your ego. It doesn’t necessarily contribute to your progression, and it may not even deepen your fulfillment from the sport.

Picture this: You walk into your local bouldering gym and at last, there is a fresh set on the wall. Before your shoes are even on, you lock onto the climb. The climb that probably isn’t the hardest problem you could try today, but it’s just hard enough for your ego to feast on. Honestly, how can a session feel satisfying if you don’t send one v“X”? Your ego eats it up like a fresh juicy burger from the Lander Bar after a long weekend in the Winds.

The real question is: How many times do you need to do this before your ego is “full”? How many v”X”s of that style do you need to tick before you are comfortable working your antistyle?

You might be unaware that your ego needs validation every time you climb. If this is true, you are not alone - and reworking this habit may bring more growth and satisfaction to your climbing.

Recognizing that you often partake in “ego “climbing and its performative satisfaction is not an easy feat.

I struggled with my own Ego Grade for quite some time. My chest would puff up every time I climbed that idealistic, beautiful 13a grade. This mindset bled into my outdoor sport climbing for the better part of five years. Admittedly, there are benefits to this challenge: I got very good at sending this grade quickly. It helped me send stacked 5.12 multi-pitch climbs and get lots of volume while on climbing trips.

Even with these successes, I truly believe it has stunted my ability to progress to higher grades and even worse, I became mentally uncomfortable struggling on almost any climb below 5.13. This stole a significant amount of enjoyment of the sport from me.

The Fighter and the Dancer

I have a friend named Nicki who is one of the most composed climbers I’ve ever seen—no grunts, no screams, not even a power peep. When we climbed together, we felt the stark differences in our style. When I went for an onsight, I gave it my all every time, sometimes kicking and screaming. Nicki, on the other hand, had a climbing habit that baffled me: while onsighting routes within her own Ego Grade, she would just... take.

It drove me nuts. "Why would you do that?" I’d ask. "You could’ve powered through and sent it. Then we could’ve moved on!" For years, I have been trying, mostly in jest, to coach her on how to try hard while onsighting. I assumed the reason she took so often revolved around the fear of falling, but I was completely wrong.

Nicki wasn’t afraid of falling, nor was she getting too pumped to continue climbing. What Nicki truly disliked was climbing through moves that feel unsure, awkward, or imprecise. She was a perfectionist and because of this, she eventually executed hard routes with grace and a deep understanding of the best movement. This type of approach requires time, and does not lend itself to onsighting. Her record shows that while she is more than capable of onsighting climbs closer to her redpoint grade, she often opts to sacrifice the onsight and work out the moves so she can climb it smoothly and confidently the second go.

After our latest climbing trip together, we finally figured it out. My ego wouldn’t let me fall on something I thought I should be able to do on the first try. On the flip side, her ego wouldn’t let her climb with imprecision.

We realized we have two completely different approaches to our own ego-inflating grade:

There's me, screaming through off-balance moves, pumped out of my mind, often successfully onsighting like an off-brand Sharma. I feel like I should send that grade quickly. So I send, regardless of how poor my movement is, because clipping chains justifies the effort. I am going to call this Fighter Mentality.

Fight·er Men·tal·i·ty:

Noun: 100% try hard, 25% technique, and is often bad at math

Photo: Ben Neilson

Signs that you might be a Fighter include:

Skipping antistyle routes because you can’t visualize the beta quickly

Your onsight/flash grade is very close to your project/redpoint grade (11c flash and 11d redpoint for example)

You often send in a way that you don’t think you could repeat again, or often “blackout” and have no idea what you did

You struggle with or don’t spend time memorizing beta

You are embarrassed if you can’t figure out the moves quickly

There is a large gap between your style grades (v7 steep compression but only v4 vertical crimping)

You give it 110% every time you get on a rope or a boulder problem.

Then there's Nicki, taking mid-route to rehearse every move even if she looks in control. Repeating a route several times, and eventually climbing like a dancer performing a beautifully choreographed piece. She feels like she must climb immaculately. So if there’s uncertainty in her beta, she won’t try hard, because imperfect execution may not yield the same level of satisfaction or achievement. I am going to call this Dancer Mentality.

Danc·er Men·tal·i·ty:

Noun: 25% try hard, 75% technique, often better at math

Signs you might be a Dancer:

Dialing in routes so much that by the time you send them, it feels like advanced walking

Your onsight grade and redpoint grade are very far apart (11b and 13a, for example)

You don’t want others (or yourself) to see you climb with sloppy beta

It is difficult to make yourself give 110% effort.

You don’t fall often and take out of uncertainty

You take a long time to redpoint something that you might be able to do more quickly

Ideally, you have a combination of the Fighter and the Dancer within you. For Nicki and I, that wasn't the case. We were too far on the ends of this spectrum and ultimately we were serving our egos more than our growth.

While being a Fighter or a Dancer has benefits, there can be unrealized consequences.

Finding the balance

The Fighter avoids learning opportunities on ego-grades and loses the chance to refine their movement skills. They skip antistyle routes because their ego can’t handle projecting a lower grade they “should” flash. The Fighter relies heavily on intuition and can easily access near-maximal try-hard.

Their true potential, however, might lie beyond these tendencies. If they embraced precision and took more time to learn movements that are not intuitive, they could likely climb harder, more efficiently, and ultimately become a more well-rounded climber.

The Dancer avoids discomfort and only sends when everything feels just right. This approach often leads to more refined ascents, resulting in a deep understanding of projecting tactics and skills. However, it often means slower progress and longer redpoint timelines. The Dancer may struggle to give 110% when a performance has not been perfected. It is important to remember that trying hard is a muscle, just like the rest of the body, and you have to train it to use it at will.

As with most things, the ideal lies in between. A well-rounded climber can quiet the ego, accept imperfection, and approach every grade as a learning opportunity. They can try hard when it counts and embrace messy climbing to get the send, while also appreciating the value in taking the time to rehearse new movements and explore different techniques. Over time, that balance will unlock the potential to send higher grades and will increase efficient climbing at lower grades.

Photo: Clayton Herrmann

I have a simple rule of thumb that indicates a balanced climber: their onsight grade is around one number grade below their redpoint grade, and their flash grade is about one letter grade above that. For example, people who project 12a can often climb 11a first try, and probably 11b on a good day with good beta. A 5.14b climber has likely practiced onsighting to the point that they can do 13a or 13b with the right beta spray, and maybe even 13b or 13c in the first few tries. Even Adam Ondra fits relatively well into the rule – he has redpointed a 5.15d and has onsighted 14+ and flashed 5.15a.

I do not fit into the rule, and I attribute that to spending too much time and mental energy on my Ego Grade. Only last year, my max redpoint grade was 5.13b, my max flash grade was 5.13a/b, and my max onsight was 5.13a. I had climbed around 50 5.13- routes… talk about a flat pyramid! This was a case of an overindulgence in the Fighter mentality. Once I had tried a route 5-10 times, I lost interest. Often I couldn’t make the hard or uncomfortable moves feel doable quickly enough. Maybe to soothe my ego, I told myself that the route wasn’t worth my time. Maybe I was simply enticed by other low-hanging fruit that was more my style.

Ultimately, I discovered this was a deficiency I wanted to work on, so I put it to the test on a 5.13c called Pumped Puppets at Donner Pass, California. Rather than visualizing sending the route within 5-10 tries in an epic fight, I tried my best to be a Dancer via a long-term approach. I told myself there was always another day and I didn’t want to send it if it felt like a fight. My mantra became: stoicism over hedonism. Delayed gratification of a perfect send over the quick hit of sending fast and loose.

I wanted it to feel perfect, precise, and stripped of the Fighter try-hard. I believed that the only way I could convince myself that 5.14 is in my wheelhouse (the lifelong goal), was to climb 5.13c without having to fight for it.

In the end, I danced on the day I sent, and had plenty of gas left in the tank. I glimpsed into the future of climbing even harder routes. The battle was not won in a day, however, and I constantly have to calm my ego to become more of a Dancer. It has been a beautiful process, and I have started to regain some of my love for climbing through removing my need to send the ego grades.

For all of us, the real questions become: when is it important to use whatever it takes to try as hard as possible, when is it important to adopt a learner mindset, how do you access those mindsets when you need them, and how do you train both muscles?

Coachable moments - The Ego and Mental Piece

There are two avenues for coaching tactics surrounding the balance of the quick send and the precision send.

For both the Fighter and the Dancer, this will likely take some head game and ego work. Some of the work will overlap for the two approaches, and some will differ.

A commonality in working through both the Fighter and the Dancer mindsets is this: Nobody really cares about your climbing. You are most likely not a professional, this is not your net worth, there is always someone better than you, and people don’t judge you nearly as much as you judge yourself. So to retrain your ego, go make a fool of yourself! Get into the gym and make a silly try-hard noise. Go jump at a hold and fall on your butt, be goofy, and most importantly teach your internal critic to be more compassionate.

Specifically for the Dancer, focus on the idea that it is okay for people to watch you (or watch yourself) climb sloppily. During your next gym session, pick out a route and either decide on the beta from the ground or go in blind and embrace whatever happens. Do your best to execute the beta you set out for yourself even if you hesitate and are uncomfortable. An even easier practice is to only climb until you fall, then come down. Cement the idea that you only get one attempt. Finally, climb on the anti-ego grade or style climbs. If you like the 5.12c or v7 vertical tech - work on the 5.11 or v4 steep compression boulders.

Specifically for the Fighter, go into the gym and be silent. No power screams, no jumping for holds, no pushing through fear or discomfort. Your goal is to stop whenever something feels awkward or uncomfortable. I would recommend top roping or climbing lowball boulders to dissuade poor climbing due to fear of falling. Finally, climb on the anti-ego grade or style climbs. If you like the 12c steep jug hauls, hop on the 11c vertical tech that makes you feel like an uncoordinated gorilla. Finally, take take take take take until you can dance your way up a climb. I want your phone to start recommending music by “a-ha” because you are yelling "take” and “on me” so often.

Coaching moments - The Planning Piece

Now that you have your ego under control (an ongoing process), I’ve included some exercises you can do at the crag to practice projecting, onsighting, and flashing climbs.

First, it is important to have a plan for your day and stick to it.

Similar to training, if you cut out parts of your plan because you don't feel like doing them, you will progress more slowly. If you show up to the crag with a plan to onsight five routes, but only try one and decide to go try your project instead, you won’t get better at onsighting. If you plan to project a route but get distracted by a different climb that is closer to your flash grade, you won’t get better at projecting. Once again, we need to find the balance:

Onsight/Flash Practice Workout- I call this “Learning How to Try Hard and Communicate with Intent”

Purpose: To help Dancers fight.

Planning: Pick 10 new routes that you and your partner have never climbed. Each partner will attempt to flash 5 routes and onsight 5 routes over the course of 2 climbing days.

Day 1: Your partner is the “onsighter” and you are the “flasher” (please don’t actually flash anyone). Your partner will try to onsight a route, hanging draws, with the goal of sending. Their secondary goal is to collect as much information for their partner, the flasher, as possible. They will try their absolute hardest, committing to not saying “take” on the attempt.

Once they are back on Earth, you and your partner will talk. Discuss where the hard moves are, what the beta options are, where the rests are, etc. Eventually, you can figure out how much beta is useful, what type of beta works for you, and how much information is overload. It can also be helpful to notice how you best receive beta - do you want the full spray-down on the ground, or a play-by-play as you are climbing?

Then you will try to flash the route, knowing that you only get to try that route once. If you fall, then pull back up and rest for 5-10 minutes and try to flash the rest of the route. No hanging around working beta or re-trying moves. Clean the draws and repeat this process on 4 more routes that day.

Day 2: Reverse roles: now you are the onsighter and your partner is the flasher. Kind of like understanding your romantic partners love language, remember that your beta spray needs likely differ from your partners. Again, you will try as hard as you can to onsight the route with the intention to help your partner flash the route later.

Day 3 (Extra Credit): Eating ice cream isn’t usually part of any real workout, but I often recommend it after a well-executed training session. So, Day 3 is the chunky monkey of this workout. On Day 3 you are free to return to any route that you did not send on day 1 or 2. Before you climb, practice discussing the beta options again with your partner, using the combined insight from both of your attempts. The second-go attempt of the routes will still require some flash or onsight practice since you won’t remember all the beta, even if you think you might. Work on being patient and open-minded, and don’t be afraid to sprinkle in some good ol’ try-hard when needed.

Some notes: This is a fantastic thing to do on climbing trips where you don’t want to spend time projecting. You can explore a lot of new areas, get familiar with the style of a zone, tick off new routes, and learn something in the process. I did this all the time with the students at The Climbing Academy for the first few days in a new zone as a way to find which crags they liked, to explore the area, but still be targeted with some form of training.

Perfectionist Practice- I call this one “No Send Sunday”

Purpose/Planning: To help Fighters dance. We are going to avoid the traps of flash-pumps and sloppy climbing with this simple drill.

Practice: Pick a specific day where you take at the first bolt of every single route on every single try. Simply eliminate the ability to send so that the fight is less likely to enter your system.

If you eliminate the ability to send, you become more likely to work on the moves at any point on the route. When you make moves that are less than optimized (dynamic when they could be static with better lower body positioning or stiff when they could be more fluid), go back and explore other options. Insert “technique, Squidward” meme. You’ve already un-sent the route by bolt one, so there is no reason to put up a fight now. Work on the mantra: “Where can I learn to dance on the route instead of fighting through it?”

A Combined Drill- I call this the “2nd-Go-Balancing-Act”

Purpose: To help both Dancers and Fighters find the balance.

Planning: This final drill encompasses both techniques, and in my personal opinion is the benchmark of a talented climber. If a climber can send something very hard on the 2nd go (or potentially the 3rd), it demonstrates their ability to combine high effort and high precision in a relatively short amount of time. Many pro climbers are incredible at this, especially if they have competition experience. They have this special (and by special, I mean they have spent loads of time training it) ability in which they gather so much beta on their first try while bolt-to-bolting a route, then come down and turn on a readily available amount of try hard to send on their second go. While this requires serious effort, it also requires incredible focus, beta finding and memorizing skills, climbing tactics, and a controlled ego.

Practice: Pick a climb that is higher than your onsight or flash grade, and lower than your redpoint grade. If you have redpointed 5.13a and onsight or flashed 5.12b, then a 5.12c or 5.12d is perfect for this. On your first go, do not spend all of your energy achieving perfection on every move, nor try to onsight the route. The goal is to spend as little energy as possible learning as many of the important moves as you can. The goal is also to learn how and where to rest, and which sections require try-hard vs. slow and controlled precision.

Go through the mental practice of committing the moves to memory while on the route. Then return to the ground and spend some time rehearsing the moves before trying again. This is the Dancer part of the drill.

After you come down and rest, then comes the Fighter part of the drill. Mix the Dancer memory you have with the Fighter try try-hard. The second go is where you give 110%. Even if you get so pumped that you can’t climb for the rest of the day remember: this is still a goal-oriented session, so that is okay and productive. Each attempt is a learning experience, and at the end of the day, it’s all money in the bank. Often a route of that grade would take someone four tries to send normally, so this is a practice in condensing four goes of unfocused effort into two goes of focused effort.

Departing Thoughts

Whether you’re a Fighter clawing through every move or a Dancer perfecting every detail, your relationship with the Ego Grade shapes far more than just your tick list; it shapes your growth.

By identifying your default tendencies and deliberately exploring the opposite end of the spectrum, you begin to unlock new dimensions of learning, progression, and joy in climbing.

The real progress often begins when the send doesn’t matter as much as how you send. If you can toggle between trying hard and refining movement, between effort and elegance, you’ll not only climb harder, but you’ll climb better. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll discover that your proudest ascents aren’t the ones that fed your ego, but the ones that challenged it.